The Lesser-Known Poe

by Christina Sampson

Every year, particularly around Halloween, middle- and high-school students shuffle into English class and are force-fed one or several of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories (and possibly some of his poems.) The students struggle through The Tell-Tale Heart, The Fall of the House of Usher, The Raven, The Cask of Amantillado or, if their teacher is particularly ambitious, poems such as Lenore or Ulalume or maybe even Annabelle Lee.

Understandably, teachers tend to gravitate towards these selections because they are among the most accessible of Poe’s works to the modern reader.

Poe, despite his deliberately aborted stint at military school, was incredibly intelligent and his personal obsession with classic German philosophical texts and mythology does bleed into many of his literary works. This results in lots of Latin and Greek phrases (often not translated). The footnotes quickly multiply and that, combined with the dated syntax and Poe’s own penchant for using the archaic definition of words, can make reading his works a daunting undertaking.

The students are also told the usual true — but grossly oversimplified — facts, often with the same, trite phrases. Poe "invented" the mystery with Murders in the Rue Morgue, he was a "master of horror," his writings were renowned for their grotesque and macabre slant, etc. etc.

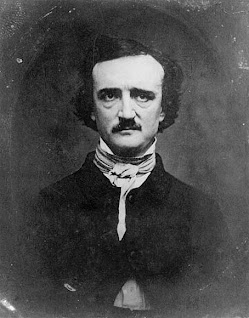

For example, take the story behind the famous, doe-eyed portrait of him that undoubtedly accompanies his section in grade-school textbooks. This famous and most widely-published portrait of Poe — in which he appears somber, wearing a dark jacket and light scarf — was taken mere days after he attempted suicide by taking laudanum.

One wonders what the person who took him to get the daguerreotype was thinking — "Sorry that didn’t work out, old chap, but let’s get a snapshot taken! Won’t that be fun!"

Sarah Helen Whitman, Poe’s main love interest after the death of his wife Virginia Clemm, called the portrait "Ultima Thule," which essentially means the very outer limits of discovery and travel. Four days later, Poe had another picture taken, which he actually gave to Whitman. She claimed it, too, failed to capture his "noble" good looks, despite his being nearly recovered by that time. (Another interesting side note: the mustache Poe is sporting is a "new" look for him at the time the portrait was taken; although we picture him mustachioed for all his life, in fact, he made it a point to be clean-shaven most of the time).

Sarah Helen Whitman, Poe’s main love interest after the death of his wife Virginia Clemm, called the portrait "Ultima Thule," which essentially means the very outer limits of discovery and travel. Four days later, Poe had another picture taken, which he actually gave to Whitman. She claimed it, too, failed to capture his "noble" good looks, despite his being nearly recovered by that time. (Another interesting side note: the mustache Poe is sporting is a "new" look for him at the time the portrait was taken; although we picture him mustachioed for all his life, in fact, he made it a point to be clean-shaven most of the time).

Many teachers will also undoubtedly fail to mention Poe’s abilities as a literary critic or his efforts as a magazine publisher, magazine editor and painter.

Also unlikely to be mentioned is Poe’s history as a bit of a ladies’ man after Virginia Clemm died, and how he was embroiled in several socially dramatic episodes involving multiple ladies, rumor mongering and the questioning of his honor.

Instead, students are given the idea that Poe had only one great love, his very young cousin, Virginia Clemm.

That being said, by no means is Poe’s place in the annals of Horror undeserved.

Still, he often gets short shrift during Halloween and it is high time for some of his other horror writings to be highlighted.

There are more ways to send chills up someone’s spine than simply scaring them with beating dead hearts and repetitive ravens, and Poe deftly handled them all, particularly horror along a more subtle, disquieting vein.

So, if you’re as tired of the same old Poe on Halloween as I am, try reading one of the four following short stories. They’re all pretty easy reading and, although in some there are similarities to his more famous works, these tales are no less enjoyable.

All quotes taken from: Poe, Edgar Allan. The Collected Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe, Random House Modern Library Edition, 1992, United States and Canada. Editors unlisted.

Biographical information: Since I’ve been reading Poe and all about him since grade school, much of the information was taken off the top of my head, as it were. However, confirmation of facts was conducted using the introduction of the above book as well as one other. It was:

Poe, Harry Lee. Edgar Allan Poe: An Illustrated Companion to His Tell-Tale Stories, Metro Books, 2008, New York.

The Black Cat

In my opinion, no other story shows Poe’s mastery of conveying a mental instability using a nervous, psychotic-twitch like narrative style than this one. With very few overt signals and no dialogue at all, the reader becomes increasingly aware with each page turned that something is very wrong with the man penning these words…and it’s probably more than alcoholism, too.

In my opinion, no other story shows Poe’s mastery of conveying a mental instability using a nervous, psychotic-twitch like narrative style than this one. With very few overt signals and no dialogue at all, the reader becomes increasingly aware with each page turned that something is very wrong with the man penning these words…and it’s probably more than alcoholism, too.

In my opinion, no other story shows Poe’s mastery of conveying a mental instability using a nervous, psychotic-twitch like narrative style than this one. With very few overt signals and no dialogue at all, the reader becomes increasingly aware with each page turned that something is very wrong with the man penning these words…and it’s probably more than alcoholism, too.

In my opinion, no other story shows Poe’s mastery of conveying a mental instability using a nervous, psychotic-twitch like narrative style than this one. With very few overt signals and no dialogue at all, the reader becomes increasingly aware with each page turned that something is very wrong with the man penning these words…and it’s probably more than alcoholism, too.

The unnamed narrator starts out as an animal lover who animals naturally gravitate towards. His wife is the same way and the two quickly establish a homestead complete with birds, a dog, rabbits, a monkey and a black cat named Pluto.

Pluto, in particular, loves the narrator, who unfortunately falls into a spiral of alcoholism. As his "disease" increases, so does an almost inexplicable distaste for the cat, who piteously follows him around the house like a puppy. One night, in a burst of drunken disgust for the animal when it avoids him, the narrator grabs Pluto and cuts out one of his eyes. This solves the problem of the cat following him around (once healed, Pluto flees in terror from the man), but not the mental instability of the man himself.

At first relieved, and even a little saddened, by the animal’s terror of him, soon the narrator again begins to feel an irrational, burning "perverseness" for Pluto. And so, "in cold blood" the narrator grabs Pluto, puts a noose around his neck and hangs him from a tree in the garden.

That night, the narrator’s house burns down….except for the wall against which the narrator put his bed. And on that wall is the unmistakable bas-relief in char of a giant black cat.

This doesn’t stop the narrator from drinking, however, and one night at a bar he comes across another black cat curled up atop a barrel of alcohol. Upon petting it, he discovers it looks almost exactly like Pluto only it has a splotch of white fur on it’s chest. It follows the narrator home where the new pet and his wife become fast friends.

Yet again, an irrational hatred of the animal arises within the narrator. The cat, however, nearly suffocates the narrator with affection: when he sits, the cat is immediately upon his lap, when he walks, the cat is always underfoot.

The narrator has enough of a conscious to refrain from acting violently towards the new household pet, until one day when it almost trips him while he is going down the cellar steps. He grabs an axe and would’ve succeeded in killing the animal, but his wife interferes. This spurs the man into a rage that leads him to bury the ax in his wife’s brain. She dies instantly.

But of course, this does not mark the end of the tale. The narrator does successfully hide the body, and even the cat disappears, but a happy ending is not be had…

This is one of the very rare stories Poe has written that features a happy ending… after, of course, some deeply disturbing events.

This is one of the very rare stories Poe has written that features a happy ending… after, of course, some deeply disturbing events.

Beginning innocuously enough, the narrator begins with what appears to be an academic monograph considering the fact that people really enjoy reading about human tragedies — ("…the Plague at London… the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, or the stifling of the hundred and twenty-three prisoners in the Black Hole of Calcutta."). He maintains that these are acceptable to people only because they are true, and that if similar stories were to be told in fiction, well, that would "disgust" the reader.

This brings him to reflect that when it comes to something horrid happening to the individual, there can be nothing more terrible than to be buried alive. Fair enough, but it soon becomes apparent that the author has an unsettling obsession with the idea of mistaken burials.

He even goes on to give us four mini-macabre tales (which honestly, make this story worth reading in and of themselves).

In the first, the wife of a respected Congressman appeared to have been struck dead by an unknown malady and was thus interred in the family vault for three years. When the vault is opened again to receive a sarcophagus, the chaotic remnants in the tomb tell a ghastly story of a fight against a horrific fate.

The woman, awakening in a coffin, apparently manages to break it open by moving around enough that if falls off the shelf it was on and breaks open. An empty lamp on the floor tells us that, for a little while at least, she had some light.

Using a piece of her coffin, the woman apparently struck against the iron door at the top of the vault’s stairs to attract someone’s attention. She died, but instead of falling down the stairs, her shroud catches on some iron work and she instead rots standing up, a grim hostess greeting those who opened the vault’s door.

The second story is a romantic tragedy with a suitably morbid twist but happy ending nonetheless.

In it, the beautiful daughter of a wealthy family rejects the love a poor Parisian journalist, instead marrying a diplomat. The decision results in forcing her to endure several years of a terrible marriage during which her husbands is horrible to her. One day, she appears to die and is buried in the village cemetery.

The Parisian journalist, ever the romantic, journeys to the grave in hopes of exhuming her body and cutting off her hair so he can keep it. While cutting off the "luxuriant tresses," the woman opens her eyes! Using "certain powerful restoratives suggested by no little medical learning," he manages to restore her to full health.

Saving her from dying in an early grave wins the woman’s heart over to the journalist and the two flee to America. Twenty years later, the couple returns to France, thinking the woman will no longer be recognized by anyone they know. Sure enough, her first husband immediately recognizes her and claims her as his. The issue goes to court and the judges decide that enough time has passed that her first husband has neither equitable or legal claim to her.

Finally, the reader is told about an artillery officer "of gigantic stature and robust health" who is thrown from a horse and fractures his skull. Eventually falling into a coma — despite being bled — he is deemed dead and buried with "indecent haste" in a public cemetery.

A passing villager, insisting that he felt the soil moving beneath him as he sat on the grave, rushes to the village to tell him. Finally, the villagers, persuaded by his insistent terror, dig up his "shamefully shallow" grave and find him alive. He is taken to the hospital and, after recovery, is even able to explain how he heard people walking on his grave and as such tried to make a commotion from within his coffin. (Poe does account for the one hole in this tale, explain that air was admitted to the "loosely filled" grave through the "excessively porous soil."

Ironically, the poor officer is then subjected to the "galvanic battery" (which, from what I can gather from this and other stories, is kind of like the pads used to shock a person’s heart back into beating… only, without either the knowledge, technology, or voltage control we have today), which kills him.

The galvanic battery plays a role in the next mini-horror story, but that one I will leave to be read by you. Trust me, it’s worth it.

Moving on to our narrator, we soon discover he has "catalepsy," a condition which essentially causes him to fall into mini-comas. We also learn that his obsession with being buried alive has taken over his life. He needs to be around people all the time, he thinks of nothing else all day and dreams of it at night. He makes his friends literally swear they will never allow him to be buried until or unless his body has actually begun to decompose.

And then, one day, he awakens to find himself surrounded by a structure on all sides, no more than six inches above his face… surely, a coffin. He either hallucinates in his terror or perhaps really does glimpse the horrors of a Hell in which every grave in the world is simultaneously flung open and millions of souls were buried too early and rustle in misery.

The ending is rather surprising, given that this is a Poe story. However, it is not unwelcome and does nothing to detract from the disquieting thoughts reading this story may lead one to have, the vivid horror imagery, or the signature way in which Poe leads the reader slowly led into the ruffled mind of his narrator.

Translation of opening quote: "The great misfortune of not being alone." – La Bruyere

Don’t let the French, German, and possibly Hebrew — or perhaps ancient Greek or Arabic — sprinkled throughout the beginning of this story scare you away. After all, Poe even translates the German for you (a courtesy not often extended by him to the reader).

The pompous, over-educated narrator of this story is sitting in a hotel café after recovering from an illness. He is reading a paper and smoking a cigar and generally basking in the mere pleasure of being alive (despite some pain) that often follows a serious illness or injury.

As evening falls, he becomes absorbed in watching the throngs of people outside the window, at first just watching them as a group, and then slowly classifying them into classes (clerks, gentry, pickpockets, etc.). Fittingly, as the day grows late, the less genteel, more harsh-featured working class citizens begin to appear while making their way home.

Then, just as a fog envelops the street, the narrator’s attention is arrested by a face of a man so fiendish, so devilish, our friend is immediately captivated by him. So much so, in fact, that he grabs his coat and hat and rushes after him.

He notices the mysterious man is dressed in dirty, but beautiful, clothes and that he is carrying both a diamond and a dagger.

The man goes to a street that is slightly less crowded and seems to aimless cross the street and change direction for no apparent reason, at one time even almost catching the narrator in the act of following him.

After following the man for a while, it becomes apparent that the man prefers to be immersed in a crowd and that; actually, being apart from a throng of people seems to cause him almost physical pain.

Our narrator follows and follows the man, finally realizing that the man literally cannot be left alone. He must be within the midst of people to be spared an agonizing pain. Having realized the horrible, personal, eternal torture of the man, he abandons his quest to follow the man.

The Corneille quote that begins this story translates to: "Weep, weep, my eyes water and melt you! Half of my life put the other to the grave."

I have a confession to make: this particular tale isn’t all that frightening, or even that disturbing by modern standards. In fact, it can also serve as an example of one of Poe’s more humorous stories, as much of the narrative is decidedly tongue-in-cheek and the action does have a vaguely comic, almost Abbott and Costello feel about it.

I have a confession to make: this particular tale isn’t all that frightening, or even that disturbing by modern standards. In fact, it can also serve as an example of one of Poe’s more humorous stories, as much of the narrative is decidedly tongue-in-cheek and the action does have a vaguely comic, almost Abbott and Costello feel about it.

Or so I thought, when I first read it in sixth grade. But somehow, I kept thinking back to it, images from the ending lingering in my brain, and the more I thought of it, the more I became aware of being a little disturbed. After all, it was possible, wasn’t it…?

I read it again. I realized that, yes, this was definitely Poe using a very wry sense of humor. It was almost like Mark Twain in the way it poked a bit of fun at the tightly regulated social rules and rituals of the gentry (I didn’t know it in sixth grade, but that makes sense: Poe was a southern gentleman, and took that station very seriously). But the image in my head at the end of the book, of that lump by the door… that wasn’t really funny at all when you thought about it. Actually, it was pretty creepy, at least to me.

But I digress.

Our narrator here is named Smith, and, by his own admission, simply can’t stand an unanswered question. One night, while at a party, Smith is introduced to Brevet Brigadier-General John A.B.C. Smith is so struck by the general’s perfect good looks and fine, refined manner that he can’t even remember who introduced them.

The two men enjoy a wonderful conversation during which the general rhapsodizes about the "mechanical age" in which they live and all the convenience machines offer.

But something nags at Smith. He can’t quite put his finger on it, but something is simply different about the general. It’s not his extraordinary good looks, right down to "the most entirely even, and the most brilliantly white of all conceivable teeth." Nor is it the general’s impeccable manners and precise way of moving (if he weren’t so obviously of high breeding, Smith muses, the general’s movements would seem cold; instead, this quality seems to reflect a natural, aristocratic aloofness).

Smith quickly sets about finding the answer the way most gentry would — by seeking out any gossip about the general from his friends. He attempts to whisper with a friend in church but the pastor — Dr. Drummummupp (get it? Drum ‘em up?) — gets so angry he almost breaks the pulpit in half by banging on it.

Smith goes to the theater to ask a couple of girls he knows but, again, is shushed by an actor (whom Smith subsequently beats up after the show). He then attends a party and asks someone who would know, but again is interrupted. He visits a friend, but the friends makes a sarcastic comment causing Smith to stalk off.

Everyone seems to agree on one thing: something positively horrid happened to the general while he was fighting against the Bugaboos and the Kickapoos (who we know only as "Indians"), the general was extraordinarily brave, and for some reason everyone also tends to starts babbling about modern times and technology.

Finally, Smith decides that he’s just going to go and ask the general himself. He is totally and utterly unprepared for who — or what? — greets him there. All his questions are answered without any real explication from the general… at least, not verbal explication.

--- Christina Sampson

SP is proud to have THE Christina Sampson as a guest writer. Because of her wonderful interest in macabre literature and enthusiasm for strange and surreal nostalgia, SP has given her an open and unlimited invitation to drop into the crypt anytime she pleases. (Hopefully, a few venomous spiders and rotting zombies lurking about won't discourage her from returning.) The Daring Damsel has worked as a journalist for the Pahrump Valley Times, Las Vegas Tribune, Courthouse News Service, and numerous other entities. To learn more about Christina Sampson, check out her website at Sampson CopyWrite or on Facebook.

The artwork featured above the article was done by the talented illustrator Abigail Larson. You can view (and purchase) some of her incredible work on her website at Abigail Larson Illustration.